My grandmother never measured anything.

She cooked by feel, by memory, by the weight of ingredients in her hands. The ribollita she made every Friday during Tuscan winters came together the same way it had for her mother and her mother’s mother before that. Stale bread, white beans, dark kale, whatever vegetables needed using up.

When I asked her to write down the recipe before she passed, she laughed. There was no recipe. There was only the understanding that nothing gets wasted and everyone gets fed.

This is my attempt to capture what she did. The measurements are approximate because that is how this dish works. The technique matters more than precision. The soup costs about €3 to make and feeds six people comfortably with enough left over for the next day.

It tastes better the second day. That is the whole point of this dish.

What ribollita actually means

The word translates to “reboiled.”

This was not a dish invented for restaurants or cookbooks. Ribollita came from Tuscan peasant women who needed to stretch a week’s worth of leftovers into meals that would sustain families through cold winters and hard labor.

The tradition worked like this. On Friday, the women gathered whatever vegetables remained from the week, added them to beans they had been cooking, and stirred in the stale bread that had gone hard. The whole thing simmered together into something between a soup and a stew.

Then it sat overnight.

The next day, they reboiled it. Ribollita. The bread broke down further. The flavors melded. The texture thickened. By Sunday, it had transformed into something almost solid, more like a savory pudding than a soup.

Some families fried the last portions in olive oil like a pancake. That version is called ribollita refritto, and it is magnificent. The crispy edges and soft center create something entirely different from the soup it started as.

Why this tradition matters now

The Italians have a phrase for this style of cooking: cucina povera, the kitchen of the poor.

It was not a lifestyle choice. It was survival. Families ate what they grew. They bartered with neighbors for what they could not produce. Meat was rare and reserved for special occasions. Every scrap had purpose.

The women who created these dishes were not following sustainability trends. They were keeping their children alive during times when hunger was a real and constant threat.

But the food they invented through necessity turns out to be exactly what modern nutritionists recommend. Whole vegetables. Legumes for protein. Minimal processing. No additives. Seasonal eating by default because that was all that existed.

My grandmother lived to 94 eating this way. Her mother made it to 91. The women in her village who cooked like this routinely outlived their husbands by decades. The food kept them strong through wars, poverty, and displacement.

Now restaurants charge €18 for bowls of ribollita and call it rediscovered peasant cuisine. Food writers describe it as sustainable and zero-waste. My grandmother would have found that hilarious. She was not being sustainable. She was being practical.

The essential ingredients

Traditional ribollita requires specific components, though proportions vary by household and by what happens to be available.

The non-negotiables:

- Cannellini beans – dried and soaked overnight, or canned in a pinch

- Cavolo nero – Tuscan black kale, the backbone of the dish

- Stale bread – dense, crusty, saltless Tuscan-style bread works best

- Extra virgin olive oil – finish generously, this is not optional

- Onion, carrot, celery – the soffritto base

The traditional additions:

- Savoy cabbage – adds sweetness and body

- Swiss chard – another leafy green layer

- Potato – helps thicken the broth

- Canned tomatoes – just a small amount for color and acidity

- Garlic – one or two cloves

- Fresh thyme or rosemary – whatever herb is growing

The bread deserves special attention. In Tuscany, bread is made without salt because of a 12th-century tax dispute with Pisa. The Florentines refused to pay inflated salt prices and simply stopped adding it to their bread. This saltless bread stales quickly, which is why so many Tuscan dishes exist specifically to use it up. Ribollita, panzanella, pappa al pomodoro—all bread salvage operations elevated to art.

If you cannot find saltless bread, use a dense sourdough or country loaf and reduce the salt elsewhere in the recipe.

The cost breakdown

I made this last week at the Mercadona near our flat in Móstoles. Here is what I spent:

- Dried cannellini beans, 500g – €1.29 (used half, so €0.65)

- Cavolo nero, one bunch – €1.20

- Savoy cabbage, half head – €0.45

- Potato, one medium – €0.15

- Carrot, two medium – €0.20

- Celery, two stalks – €0.25

- Onion, one large – €0.15

- Canned tomatoes, 400g – €0.55 (used half, so €0.28)

- Garlic, two cloves – €0.05

- Stale bread – free, from the loaf going hard on the counter

Total: €3.38

This made enough soup for six generous servings, with leftovers for the next day. The olive oil drizzled on top adds cost, but that comes from the bottle we keep anyway. Even counting that, the cost per serving stays under €0.70.

When I think about what €3.38 buys at a fast food restaurant, the comparison feels absurd. One person gets one meal versus six people getting filled.

The full recipe

Ingredients (serves 6)

For the beans:

- 250g dried cannellini beans, soaked overnight

- 1 bay leaf

- 1 whole garlic clove

- 1 small potato, peeled

For the soup:

- 4 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil, plus more for serving

- 1 large onion, finely diced

- 2 carrots, finely diced

- 2 celery stalks, finely diced

- 2 garlic cloves, minced

- 200g canned whole tomatoes, crushed by hand

- 300g cavolo nero, stems removed, leaves roughly chopped

- 200g savoy cabbage, roughly chopped

- 200g Swiss chard, roughly chopped (optional)

- 300g stale crusty bread, torn into chunks

- Fresh thyme or rosemary sprigs

- Salt and black pepper

- Parmesan rind (optional, for extra depth)

Instructions

Step one: Cook the beans.

Drain the soaked beans and place them in a large pot. Add the bay leaf, whole garlic clove, and peeled potato. Cover with cold water by about 8 centimeters.

Bring to a boil, then reduce to a gentle simmer. Cook for 45 minutes to one hour, until the beans are completely tender. They should crush easily between your fingers.

Remove from heat. Take out the potato, bay leaf, and garlic. Mash the potato into the cooking liquid. Remove half the beans and set aside. Blend the remaining beans with their liquid until smooth. This becomes your base.

Step two: Build the soffritto.

In your largest pot or Dutch oven, heat the olive oil over medium-low heat. Add the onion, carrot, and celery. Cook slowly for 15 to 20 minutes, stirring occasionally, until everything is soft and beginning to caramelize.

Add the minced garlic and cook for one minute more. Add the crushed tomatoes and cook for another 10 minutes, letting the liquid reduce slightly.

Step three: Add the greens.

Add the cavolo nero, savoy cabbage, and Swiss chard to the pot. It will look like far too much. It will cook down dramatically.

Stir to coat everything in the tomato mixture. Add the blended bean purée and enough water to create a soupy consistency. Add the thyme or rosemary sprigs and the Parmesan rind if using.

Bring to a simmer and cook for 30 minutes, stirring occasionally.

Step four: Add the bread and whole beans.

Tear the stale bread into rough chunks. Stir them into the soup along with the reserved whole beans.

Continue cooking for another 15 to 20 minutes. The bread should absorb liquid and begin breaking down, thickening the soup considerably. Add more water if it becomes too thick. Season generously with salt and pepper.

Step five: The essential rest.

Remove from heat and let the soup cool to room temperature. Cover and refrigerate overnight, or for at least several hours. Eight hours minimum if you can manage it.

This step is not optional. The soup transforms during this rest. The flavors meld. The bread breaks down further. The whole thing becomes more than the sum of its parts.

Step six: Reboil and serve.

The next day, return the soup to the stove. Add a splash of water if needed and bring to a gentle simmer. Cook for 10 to 15 minutes, stirring frequently.

Ladle into bowls. Drizzle generously with your best olive oil. This is where the good stuff matters. Add freshly cracked black pepper. Serve with more crusty bread for dipping.

The variations worth knowing

Summer ribollita uses zucchini and summer squash instead of the heavy winter greens. It is lighter but still satisfying.

Ribollita refritto takes leftover ribollita that has become very thick, presses it into a skillet with olive oil, and fries it like a pancake until crispy on both sides. This was my grandfather’s favorite version.

Quick ribollita uses canned beans and skips the overnight rest. It works when you need dinner in an hour, but the depth of flavor suffers noticeably.

Vegetarian ribollita is the traditional version. The Parmesan rind adds depth but is not essential. The dish stands on its own without any animal products.

The mistakes to avoid

Do not use fresh bread. The stale bread absorbs liquid and breaks down in a way that fresh bread cannot replicate. If your bread is fresh, cut it into cubes and dry it in a low oven for 20 minutes.

Do not skip the soffritto time. Those 15 to 20 minutes of slow cooking build the flavor foundation. Rushing this step produces a flat-tasting soup.

Do not serve it immediately. The reboiling is the entire point. A ribollita eaten the same day it is made is just vegetable soup with bread in it.

Do not be stingy with the olive oil. The final drizzle is not decoration. It is an essential component that brings the whole dish together.

Do not make a small batch. This soup improves with scale. The larger the pot, the better the result. Make enough for several days and let the magic compound with each reheating.

What we actually eat

In our household, ribollita appears every two weeks or so during the colder months.

I make it on Friday evening, let it rest overnight, and serve it Saturday for lunch. The leftovers become Sunday dinner and Monday lunch. By Tuesday, what remains goes into the skillet for ribollita refritto.

My son, who is 13 and suspicious of most vegetables, eats this without complaint. The bread softens everything into a texture he accepts. The olive oil makes it rich. He does not realize he is eating an enormous quantity of kale and beans.

My husband takes containers to work. His colleagues, Spanish taxi drivers who know good food, have started requesting it. They recognize real food when they taste it.

The dish costs almost nothing. It requires no special equipment beyond a large pot. It uses ingredients that keep well and vegetables that grow in winter when little else does. It fed Tuscan peasants through centuries of hardship and two world wars.

It can feed your family too.

The honest assessment

Ribollita is not fast food. The full process takes two days if you include the bean soaking and overnight rest.

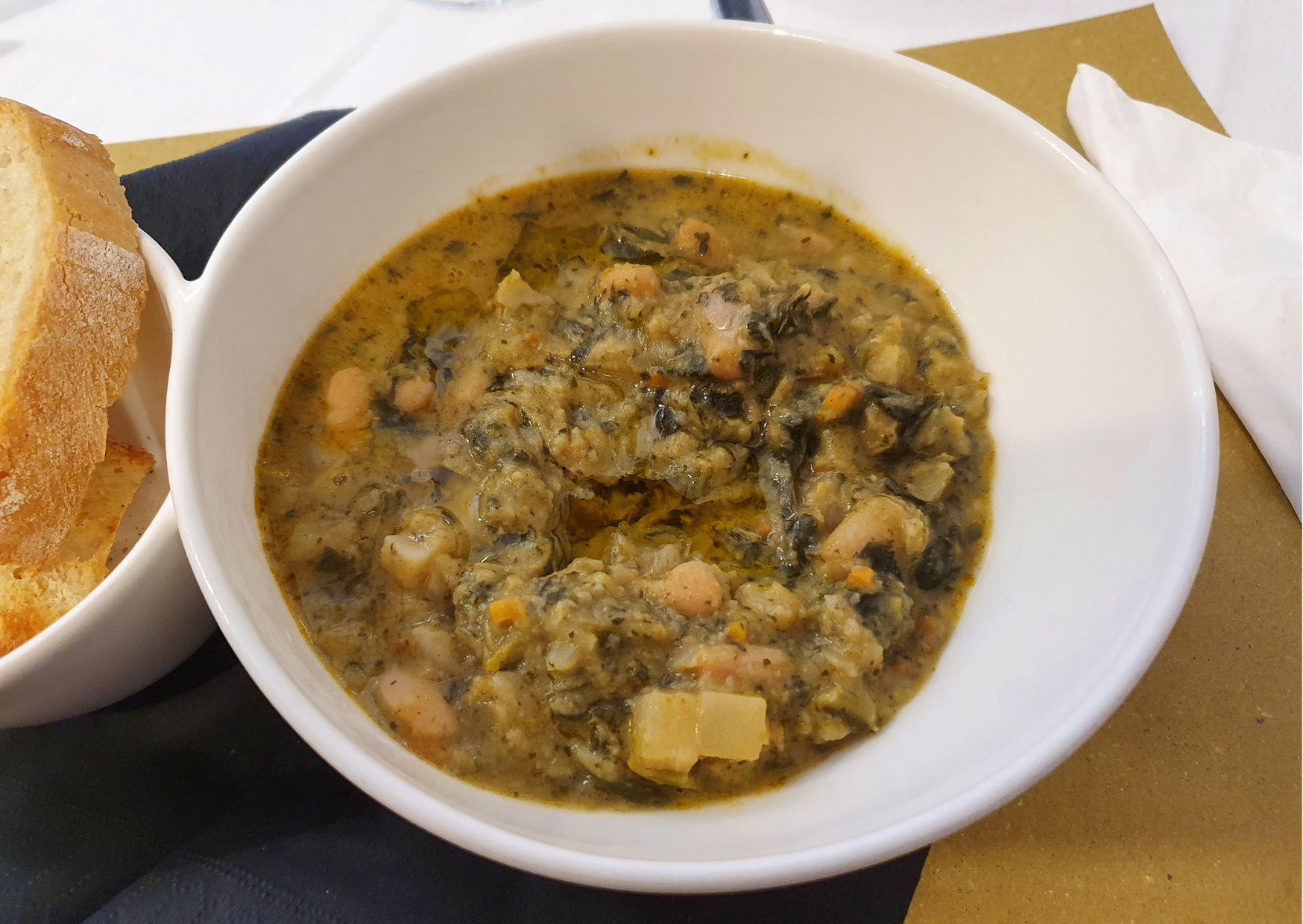

It is not glamorous. The color is murky green-brown. It photographs terribly. Instagram would never understand.

It does not work for small portions. The chemistry requires volume. Making ribollita for one person defeats the purpose.

But for feeding a family on a budget, for creating something nourishing from simple ingredients, for connecting with a tradition that sustained generations through real hardship—there is nothing better.

My grandmother measured nothing because she had done it so many times that measurement became unnecessary. She knew by feel how much bread the pot could absorb, how much oil the soup needed, how long the soffritto should cook.

I am still learning. Twenty years of making this dish and I am still learning.

That is the other thing about cucina povera. The recipes are simple, but mastering them takes a lifetime. The technique becomes instinct only after years of practice.

Start where you are. Make the soup. Let it rest. Reboil it tomorrow. Taste what happens when time and simple ingredients do the work that money and complexity cannot.

Quick reference recipe card

Ribollita (Tuscan Bread and Bean Soup)

Prep time: 30 minutes plus overnight soaking Cook time: 2 hours plus overnight rest Serves: 6 Cost: approximately €3

Ingredients:

- 250g dried cannellini beans, soaked overnight

- 300g cavolo nero

- 200g savoy cabbage

- 300g stale crusty bread

- 1 onion, 2 carrots, 2 celery stalks (soffritto)

- 200g canned tomatoes

- 4 tbsp olive oil plus more for serving

- Bay leaf, garlic, thyme, salt, pepper

Method:

- Cook beans with bay leaf, garlic, and potato until tender (1 hour)

- Blend half the beans; reserve half whole

- Sauté soffritto slowly (15-20 minutes)

- Add tomatoes, greens, bean purée; simmer 30 minutes

- Stir in bread and whole beans; cook 15 minutes more

- Rest overnight in refrigerator

- Reboil next day; serve with generous olive oil

Notes: Tastes better each day. Keeps 5 days refrigerated. Freezes well before adding bread.

About the Author: Ruben, co-founder of Gamintraveler.com since 2014, is a seasoned traveler from Spain who has explored over 100 countries since 2009. Known for his extensive travel adventures across South America, Europe, the US, Australia, New Zealand, Asia, and Africa, Ruben combines his passion for adventurous yet sustainable living with his love for cycling, highlighted by his remarkable 5-month bicycle journey from Spain to Norway. He currently resides in Spain, where he continues sharing his travel experiences with his partner, Rachel, and their son, Han.